By Raj Prabhu, Alfonso Velosa III

.jpg)

Raj Prabhu Alfonso Velosa III

India¡¯s recent release of its selection guidelines for grid-connected solar projects under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) was an important first step in achieving the JNNSM goal of creating an enabling policy framework to achieve 20 GW of solar power by 2022. As the policy has started taking shape, you can¡¯t avoid noticing that the guidelines reflect the overarching objectives of developing clean solar power and addressing power shortages while attempting to please all stakeholders. India¡¯s recent release of its selection guidelines for grid-connected solar projects under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) was an important first step in achieving the JNNSM goal of creating an enabling policy framework to achieve 20 GW of solar power by 2022. As the policy has started taking shape, you can¡¯t avoid noticing that the guidelines reflect the overarching objectives of developing clean solar power and addressing power shortages while attempting to please all stakeholders.

This policy is a good starting point for India as it delivers a clear statement about the government¡¯s commitment to providing its population with energy, and in particular, from a renewable source. It also provides a core set of definitions and policy terms for the country as a whole that the states and developers can use.

Yet, as we focus on the details for this short analysis, there are several areas that stand out in the guidelines which cause us to concern about their potential impact on the eventual success of the Solar India program.

PV & CSP Ratio

In dividing the allocation of 1 Gigawatt (GW) of solar projects at a 50:50 PV to CSP ratio, JNNSM is trying to encourage the use of both technologies. By allotting specific quotas, the JNNSM is dictating the ratio of technology that can be built rather than allowing the market to select the most efficient and cost-effective technology for India. On a global scale, PV installations exceed CSP installations by a ratio of over 20 times.

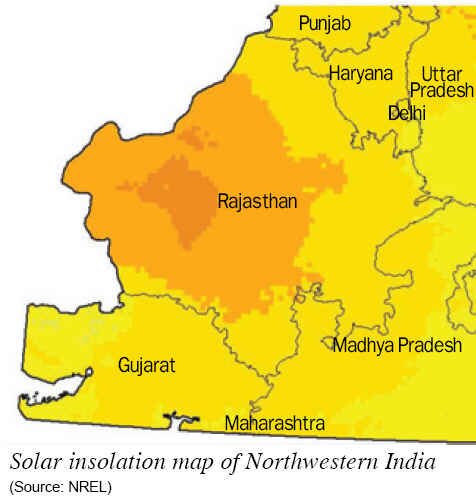

CSP technology is land and water intensive. CSP is only suitable in some areas (primarily Northwestern India) due to the quality of direct normal solar irradiation. Water availability in these areas is also scarce. Water needs for parabolic trough is about 3,000 liters per megawatt hour (L/Mwh) and about 2,000L/Mwh for central towers. Alternatives to water-intensive CSP technologies include dry cooling systems, which are less efficient and increase costs; and dish stirling systems which are commercially unproven for large-scale projects. These issues may be overcome as newer technologies become available.

Phasing Allocations

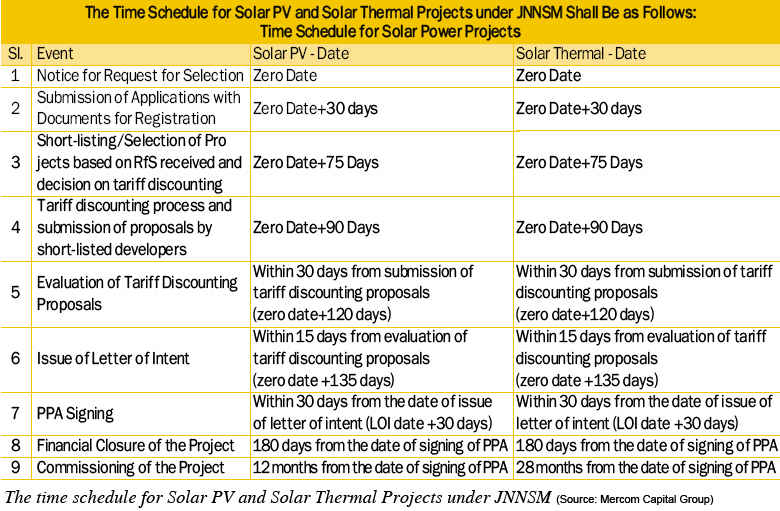

The JNNSM is allocating capacities for Phase 1, over two batches: batch 1 in FY 2010-2011 and batch 2 in FY2011-2012. The total capacity of Solar PV projects selected in Phase 1 is limited to 150 MW. Solar PV projects selected for the remaining capacity (350 MW) will be done in the second phase for FY 2011-12. The selection of Solar Thermal Projects for the entire capacity of 500 MW, less migrated projects, will be done in FY2010-11. The JNNSM is allocating capacities for Phase 1, over two batches: batch 1 in FY 2010-2011 and batch 2 in FY2011-2012. The total capacity of Solar PV projects selected in Phase 1 is limited to 150 MW. Solar PV projects selected for the remaining capacity (350 MW) will be done in the second phase for FY 2011-12. The selection of Solar Thermal Projects for the entire capacity of 500 MW, less migrated projects, will be done in FY2010-11.

Taking a lesson from other markets like Spain, JNNSM is trying to avoid a ¡®rush¡¯ by controlling the allocation of projects and phasing them in over a period of time. 150 MW for solar PV during the initial allocation is already being perceived as a disappointment to the industry. When you take into consideration the 50:50 ratio between PV and CSP, the economies of scale will be too small to bring down costs and increase efficiencies. These factors could cause investors to take a wait and see approach before making large investments without knowing how big the eventual market potential will be or when the market will develop to a certain size.

Instead of looking at this market as 1 GW by 2013, it is now perceived as 500 MW due to the 50:50 split between PV and CSP. 500 MW over 3 years (approximately 165 MW a year) for PV is not large by global standards.

Restricted Number of Applications

Restricting the number of project applications to one (1) per company with a cap of 5 MW for PV is a big blow to serious project developers with long-term growth strategies to develop projects under JNNSM. This guideline could seriously slow down the entire program. It could also make it difficult for these project developers to raise capital as growth will be limited and uncertainty remains as to future allocations in the next phases of JNNSM. Solar India needs large-scale development and the caps and restrictions need to be lifted to achieve 20 GW by 2022.

Domestic Content

The domestic content guideline looks better than what was originally proposed. Currently, only crystalline silicon (c-Si) modules are mandated to be procured domestically for 2010-2011 and both cells and modules for 2011-2012.

Developers are not allowed to procure the cheapest and most efficient c-Si modules available anywhere in the world. This raises the risk and uncertainty for investors as they have to spend approximately 84.5 crores (~US$18.8M) for a 5 MW project (per JNNSM) about half of which will go towards the purchase of c-Si modules--but they will be told which modules to buy. Ontario, a province in Canada, is trying a similar policy and is already being threatened by the European Union and Japan in the World Trade Organization. JNNSM is putting Indian manufacturers in a difficult situation. The allotted capacity per year is too small and manufacturers will have to continue to depend largely on export markets, while avoiding unwanted attention from trading partners and countries. Promised efficiencies due to economies of scale will not be realized at these low levels.

Connectivity with the Grid

The policy calls for plants to be designed for interconnection with the State Transmission Utility (STU) at a voltage level of 33 kV or above. Further, the interconnections should be at the substation (substation should be 33kV/132 kV or higher voltage levels) and not the distribution substation. The project developer should indicate to the TRANSCO the location (Tehsil, Village and District as applicable) of its proposed project. The policy ensures that the PV system owner gets connected to the grid based on their local conditions.

The impact of a large amount of electricity from an intermittent power source, such as PV or CSP, on the overall electricity grid still needs to be factored in. Although the risk of this is low for PV, since the systems are small and dispersed and should not have the same weather induced load fluctuations, there may be a bigger issue for the larger CSP projects. This could potentially lead to problems during peak usage periods. Power fluctuations and brownouts need to be addressed as inverters can shut down, shutting the power production during the time of most need and leading to significant revenue losses.

An additional factor relates to the frequency of power-out periods unique to the Indian electricity grid. On an average day, there are often several periods with brownouts or blackouts--that may add up to hours during critical hours of performance for solar systems. For a solar system to generate its return, it needs transmission capabilities or storage. Either of these situations increases the risk and cost for a PV system and lowers the return for system developers and system investors. It will also raise a concern of accuracy of measurement for solar system output in order to qualify for the government feed-in tariff payment. This may require the services of 3rd party monitoring solutions.

Selection of Projects (Bidding)

By introducing bidding, the JNNSM makes the feed-in tariff (Rs. 17.91) immaterial as it becomes just a starting point to bid. (After a 15% discount or more, state feed-in tariffs start to look attractive.) There are no qualifications or expertise needed to be a PV developer. There is a stiff bid bond implemented to curb aggressive bidding. In the case of PV, since there are no qualifications or eligibility requirements for project developers, the lowest bid still wins. As evidenced in Spain and other countries, lack of expertise and qualifications among project developers can lead to poorly executed projects, producing at much lower capacities

The other side of the argument is that project owners get paid for only what they produce. However, with India¡¯s unique power situation and severe power shortages, the goal should be to maximize production.

Role of State

Land Acquisition

Land in India is a scarce commodity and land acquisition and permitting can take considerable time. With CSP projects getting the same allocation as PV (500 MW), there will be a larger requirement for land. Land requirements for CSP projects are often double that of PV. How states handle land allotments will be an important issue.

Water Allocation for CSP Projects

It is again surprising that the solar mission decided to allot CSP 500 MW in the first phase instead of letting the markets select the most cost-effective and efficient technology.

India has a severe shortage of water. Water intensive CSP projects may not be a sustainable source of power in many parts of the country. The most conducive areas for CSP is the northwestern part of India especially in the Rajasthan desert. Water availability in these areas is scarce. CSP developers will need to secure water rights and ensure continuous water availability for 25 years. Water requirements for parabolic trough and Fresnel can be about 3,000L/Mwh and central towers consume about 2,000L/Mwh of water. Alternatives to water-intensive CSP technologies include dry cooling systems, which are less efficient and increase costs; and dish stirling systems which are commercially unproven for large-scale projects.

We have addressed some of the growing pains of developing a successful solar energy policy, but the formula for success lies in realizing what needs to be rectified and doing so quickly. It all comes down to execution. Looking at India¡¯s history of only achieving about 50% planned power capacity in the last 15 years and considering India needs approximately 15-20 GW of new power capacity added every year to keep up with the demand, there is no margin for error.

Raj Prabhu is Managing Partner at Mercom Capital Group (http://www.mercomcapital.com/) and Alfonso Velosa III is Research Director at Gartner (http://www.gartner.com/).

For more information, please send your e-mails to pved@infothe.com.

¨Ï2010 www.interpv.net All rights reserved.

|